I wrote the Imperial agent for Star Wars: The Old Republic because nobody else wanted it.

That’s not actually true, of course. There were other writers who were interested and willing to take on the task. But as it happened, they were more interested in other classes while I was most interested in the odd duck of the lot–the one class that didn’t correspond in a neat, one-for-one fashion with a classic Star Wars archetype.

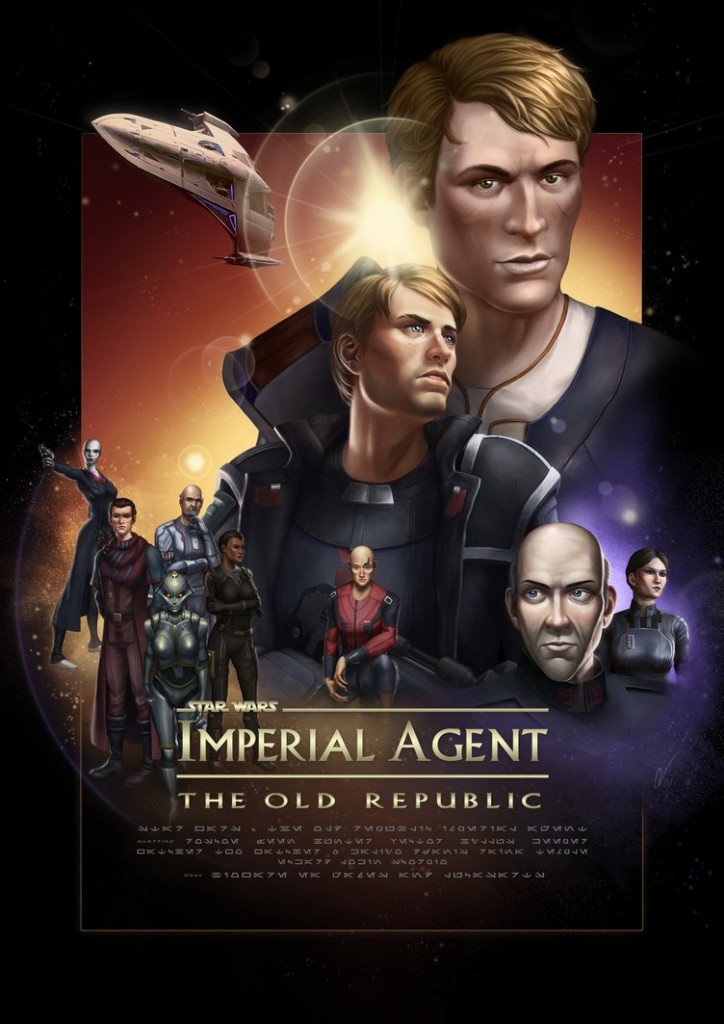

The talented Fanny Holmberg created this fantastic poster based on the Imperial agent story. She was kind enough to let me reproduce it here. Full-size version available through the link.

Which isn’t to say that the Imperial agent doesn’t fulfill a role in the Star Wars setting. The agent is the Imperial everyman, representing every background officer and ordinary citizen who supports his or her tyrannical nation. The agent is the person hoping he or she won’t be choked to death by Darth Vader for someone else’s mistake. Of course, “average citizen” or even “fleet officer” wouldn’t make a very playable class for a game like SWTOR; therefore, the Imperial agent serves as a combination of this concept with the rich (albeit background) espionage plotlines of Star Wars.

I won’t belabor this particular point, as I discussed it at length on the SWTOR website. Alas, the original article has been lost to redesigns, but is available via the Wayback Machine here–I encourage folks interested in how the agent relates to the larger Star Wars universe to take a look.

In any event, I wanted the agent for myself largely because of that lack of an obvious Star Wars predecessor archetype. It meant the class would appeal to fewer players, perhaps–but it also meant I had a freer hand in developing what the class meant. The Jedi Knight had to fight Sith and the Sith classes had to come into conflict with their masters–players were coming to the game looking for a recognizably Star Wars experience, and they’d be rightfully disappointed if at least some of their expectations weren’t met.

But with the agent, no one knew what to expect. Which meant we had plenty of opportunities… and plenty of rope to hang ourselves with.

(And I say “we” because, in the end, everything that went into SWTOR was a collaborative effort. In particular, much credit should go to Daniel Erickson–as Lead Writer from the start, he reviewed every plot summary and every line of dialogue. And if something wasn’t working, it didn’t make it past him.)

So we had our two halves, broadly defined by Star Wars without being all-encompassing. The Imperial half was, as mentioned, the Imperial everyman–with shades of Grand Moff Tarkin, the one non-Sith capable of “holding Vader’s leash” and an equal among the mightiest of the mighty. The espionage half was more ambiguous–we knew what spies in Star Wars did (steal superweapon plans, disguise themselves, snitch to stormtroopers), but not so much who they were.

The agent started out with a heavily James Bond flavor. Which makes sense, of course–Bond is the pop culture spy, and draws from the same over-the-top, pulp style of drama that Star Wars itself draws from. But Bond’s generally upbeat tone didn’t seem entirely right for a character doing dirty deeds for a morally abhorrent government. In the real world, international espionage tends toward moral ambiguity even for the most benevolent nation–portraying the Empire’s covert operations as a romp felt almost ghoulish.

We kept the agent cool, seductive, and laden with tech gimmicks–some of the spy traits most associated with Bond. We also took pages from more serious, “gritty” modern espionage works as well–24, the Jason Bourne films, Spooks, La Femme Nikita, etc. We looked to the real world Nazi SS and (perhaps even more so) the Soviet KGB.

(Fans of the Star Wars Expanded Universe will rightly point out that there have been a number of fleshed-out spies in Star Wars books and comics, too. This is true–and I’ll touch on those created by John Ostrander in my next post–but none, no matter how well-written they were, have penetrated the pop culture mainstream. Nor, I confess, am I as deeply familiar with the EU as some of my former colleagues–so I’m sure certain sources were left unplundered.)

I’m a strong believer in psychological realism–characters may perform unbelievable feats in mad circumstances, but they ought to react to those feats and the pain they endure in a relatable way. Which meant I wanted stories for the Imperial agent that took a toll; even in the best of cases, it seemed wrong that someone could work inside the guts of an evil empire and never be worn down or scarred. Living a life of lies, disguises, and treachery–for any cause, no matter how just–ought to change a person, and I wanted to to focus on that. An entirely light side agent would be possible, as would an entirely dark side one, but I wanted the story to challenge players who stayed true to ideals over pragmatism.

A fan put this trailer together during the game’s beta. I thought this seemed like a good excuse to post it.

But back to inspirations. The individual chapter storylines were designed to gently emulate different subgenres of spy fiction. Chapter one was the modern-day, gritty anti-terrorism story–24 or Bourne. Chapter two was a split between a Bond-style romp–big, flashy villains and mad science–wrapped in a psychological envelope in the style of The Prisoner and The Manchurian Candidate. Chapter three was the global conspiracy storyline–the sort seen in video games like Deus Ex and Metal Gear Solid. (That’s not to say the chapters were directly based on these particular works–rather, they’re examples of the larger subgenres the chapters fit into.)

Still, not every source we drew from for the Imperial agent was about modern day, “realistic” espionage. In my next post, I’ll run down some of the science-fiction spy fiction I took particular inspiration from.