We’ve touched on player motivation before, but let’s briefly give it our full focus. Boiled down to a simple statement, bridging the gap between player motivation and player character motivation is one of the the most important factors in a game narrative’s success.

(Success, in this case, being shorthand for “ability to elicit the desired audience reaction,” which should be broad enough to cover both “making the player cry” and “increasing the player’s engagement with the game setting and thereby the player’s willingness to spend money on microtransactions.” We’ve got a big tent on this site, with room for everyone.)

In traditional storytelling media, writers are concerned with finding ways to make the audience empathize with the protagonist. And for good reason–even when an audience may not want a given protagonist to succeed at her goals, we should care about her fate and the fate of secondary characters (otherwise, what’s the point?) It’s difficult to care about a character we’re unable to understand or relate to.

In interactive narrative, empathy continues to play a role–but it’s intimately tied to the player’s own motivation. Unlike in traditional media, where the audience is essentially passive, video game players must constantly and determinedly exert effort in order to drive the narrative forward. If I (as a player) don’t spend an hour of my life struggling and figuring out how to win a boss battle, then the player character doesn’t get to the next stage of the story.

As a consequence, the more a player’s motivations diverge from those of the player character, the more difficult it is for the player to empathize and immerse herself in the player character’s head. The opposite is true as well: the better synchronized a player’s motivations are with those of the player character, the more natural the player finds empathy and immersion. When I loathe an antagonist and the player character loathes the same antagonist, it’s deeply satisfying when we finally overcome the foe. If I like an antagonist the player character loathes, my interest in overcoming a thousand obstacles to defeat the enemy dwindles. That doesn’t mean, however, that matching motivations precisely should be an overriding goal. (We’ll get to that part shortly.)

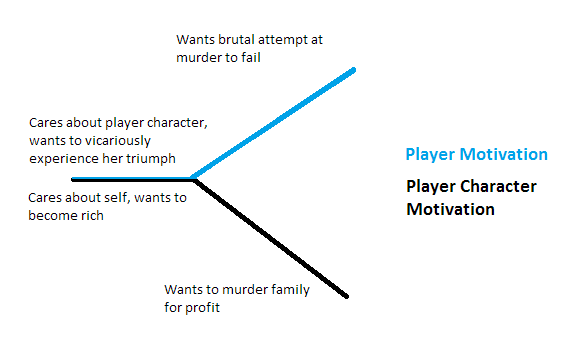

Let’s look at some theoretical examples. First, an extreme case to illustrate the worst-case scenario.

♦ ♦ ♦

“Drug Murderer,” a modern-day stealth-action game.

The player character is a successful drug dealer. By murdering a judge and his family, the player character hopes to postpone a trial that could implicate her. She must fight her way past police guarding the judge’s house and kill everyone.

In a traditional storytelling medium, this would be a difficult scene to pull off–but if the protagonist were sufficiently developed and compelling, the audience might still care enough about her to want to see the outcome. (Or loathe her enough to want to see her fail–either way, the audience is invested.) The audience doesn’t have to want her to murder the family for there to be dramatic tension–the question of how far she’ll go, whether she’ll succeed, what happens after, and so forth are all potentially engaging questions.

In a video game, where I’m the one pulling the trigger and agonizing over how to get through the bathroom window without the family dog alerting the cops–where I’m the one who has to work to make the protagonist succeed–I’m as likely as not to wonder why I’m even bothering. I may care about the player character, and I may believe that this is a crime she’d commit, but that doesn’t mean I approve. What I really want is for her to surrender to the cops, or change her mind and go home, or find some other alternative. Instead, the only way I can advance the game narrative is to put in the effort to do something I don’t want to do.

(Or maybe I do want to do it, if the gameplay is compelling and fun enough and I can ignore the narrative implications… but we’ll get to that shortly, too.)

(Or maybe I do want to do it, if the gameplay is compelling and fun enough and I can ignore the narrative implications… but we’ll get to that shortly, too.)

Generally speaking, this isn’t a bold artistic move that makes me complicit in the crimes of the player character. It’s a failure to acknowledge player motivations that simply makes me frustrated and less interested in the story. It asks the player to stop caring about why he’s doing things and to just do them to move things forward. (This is one example of the much-ballyhooed-but-still-genuinely-useful-as-a-term “ludonarrative dissonance.”)

This isn’t to say a scenario like what’s described above could never work, but it’s a challenge. Still, it’s an extreme case, and most player / character motivation issues in games are more subtle.

Suppose the protagonist of Drug Murderer is committing all the same acts but is also working with the CIA to expose a group of heroin-producing terrorists, and thus acting with sanction; this is a more likely plot for a video game (simply given marketability and what sorts of stories sell), but it has the same problems in a less blatant form. Or perhaps the protagonist is committing all her atrocious acts in order to rescue her uncle, held hostage by other dealers–an uncle given a decent amount of development and screen time, but not a character so compelling that most players would cross any line to save him. Beware the point where the player decides, “No–I’d actually kind of prefer to fail here, all things considered. The characters think the end goal is worthwhile, but I don’t.”

After that, the player must either divorce his narrative engagement from gameplay entirely (at which point, the gameplay interaction represents little more than the “interaction” of turning pages in a book to progress the story) or submerge himself in the player character’s mind so fully that he can proceed without revolting against the tasks he must perform–not impossible, but difficult, and something many players may not be interested in trying at all. Broadly speaking, it’s my belief that player motivations and player character motivations should, at a minimum, converge, even when they do not overlap.

A disconnect needn’t come about for moral reasons, either. If Drug Murderer presents a series of side tasks requiring the player to do a great deal of work to romance a secondary character, those tasks become busywork unless the player actively wants the romance to succeed (because the player likes the secondary character, sees the tasks as not excessive, etc.)

In other cases, the motivational disconnect may not be about in-world preferences at all. Let’s look at another example.

♦ ♦ ♦

“Dragon Swords VII: The Chaos Daemons,” an open world fantasy role-playing game.

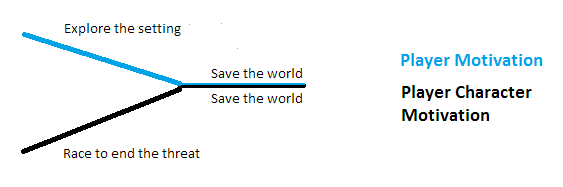

The player character (built from a variety of custom gender / race / class combinations by the player) must save the world from the evil chaos daemons by closing the fabled Daemongate in Blackmoor Swamp.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that the game narrative successfully creates a degree of player investment in the world–that is, the player would rather see the world saved than not. (After all, without at least competent writing the rest of our problems don’t matter.)

In this scenario, we have clear agreement between player and character motivations on the ultimate goal of the game. Everyone wants to save the world. The disagreement comes in methodology. As mentioned above, Dragon Swords VII is an open world game–its environments are elaborate and expansive, filled with lovely hidden touches and hundreds of side quests. Players can entertain themselves for hours just following caravans down the setting’s roads. (Dragon Swords VI: Eye of Darkspine was an ill-advised foray into action-adventure, and the less said about it the better.)

So while the player character is motivated to get to Blackmoor Swamp and save the world quickly, the player is likely to want to spend as much time exploring the setting as possible before finally, reluctantly, finishing the last of the side quests and heading for the endgame.

It’s not a disastrous difference. Our lines converge, and the points farthest apart still aren’t as far separated as in Drug Murderer. But maybe we could make it better? Maybe we can tweak our game’s scenario to encourage a closer relationship between player motivation and player character motivation.

It’s not a disastrous difference. Our lines converge, and the points farthest apart still aren’t as far separated as in Drug Murderer. But maybe we could make it better? Maybe we can tweak our game’s scenario to encourage a closer relationship between player motivation and player character motivation.

So let’s say instead that in order to close the Daemongate at Blackmoor Swamp, the player must first accomplish two things: First, he must unearth a series of lost stores of mystical knowledge buried across the land (plot coupons), searching for clues to their location along the way. Second, he must weaken the daemons’ power–they feed on conflict–by bringing peace to the land, doing everything from ending wars to helping the desperate and impoverished.

Suddenly, the player character has a reasonable motivation to explore the world in detail and perform hundreds of side quests. Sure, it’s not a perfect match, but we’re a lot closer–and maybe close enough, depending on the overarching goals of the project and other aspects of the narrative.

Is there a scenario where we can make the player’s motivation to explore the world match precisely with the player character’s desires? Certainly it’s possible. Consider a game in which the player character is, literally, an explorer–a stranger from another land come to see what’s out there and gain the knowledge and riches of another culture. But that’s a game with a very nontraditional approach to video game fantasy, and there’s nothing wrong with liking both epic save-the-world plots and open worlds. Perfect implementation of any narrative technique isn’t always optimal for a project as a whole; and sometimes “good enough” is, in context, the best you can do given the goals of the project.

Now let’s look at one more example, this time focused on dissonance caused by game mechanics (as opposed to overall gameplay or narrative factors).

♦ ♦ ♦

“Manual Transmission II: Speed Limit – Infinity,” a racing game with a story-driven campaign mode.

The player character is an internationally known race car driver who can outrace anything–except his own dark past. He must take on a series of challenging courses and win in order to pay off his mysterious backers. Numerous “achievements” requiring the player to, e.g., hit birds on the course, sideswipe all opponents, and complete a race without leaving first gear bring replayability to the courses.

Do I even need to go into detail as to why this causes a player / player character split?

Some achievements might still require the player to finish the race, too–but not most of them. Replace “Hit all the birds” with “Unlock all the achievements” if you prefer.

Some achievements might still require the player to finish the race, too–but not most of them. Replace “Hit all the birds” with “Unlock all the achievements” if you prefer.

But does it matter?

In a game with minimal story focus, these achievements don’t cause a great deal of damage–who cares about the narrative consequences if the narrative only exists as a framing device for the gameplay? No one complains that chess doesn’t dramatically emulate medieval warfare beyond the names of the pieces.

But the more important the story becomes, the more of a distraction they potentially present. Consider if the aforementioned Drug Murderer had an achievement requiring the player to give money to every homeless person in the city, or if Dragon Swords VII had an achievement requiring the player to only jump, never walk anywhere?

And of course, achievements are simply the easiest target when it comes to game mechanics encouraging action opposing or tangential to player character motivations. Crafting systems in otherwise heroic RPGs often fall into this territory–while it’s not outright wrong for my world-saving archmage to spend vast amounts of time looking for plants in the forest to dye his robe a new, awesome color, it’s not exactly a player / character motivation match, either.

On the other hand, achievements and optional challenges can also reinforce a bond between player and player character motivations. In Thief: The Dark Project, the player takes the role of Garrett, a master thief renowned for his ability to slip in and out of any place undetected. While the game’s lowest difficulty setting permitted the player to complete missions even while hacking her way past guards and alerting half the town, the highest difficulty required the player kill no one (along with stealing more treasures, completing additional objectives, and so on)–just like a proper master thief would. In essence, the game asked the player to try playing as much like Garrett as possible, but didn’t force so precise a match on players who wanted another playstyle.

(“Say,” the eccentric reader may now ask, “why did you switch from using fake games in your examples to using a real one like Thief?” My answer: I’m not here to be negative, and while I needed examples of narrative done wrong, I didn’t want to hold up someone else’s work for excoriation. But I’m happy to praise success stories, and Thief was a perfect example of what I wanted to illustrate.)

Similarly, Manual Transmission II could improve a player’s narrative engagement and immersion by making its achievements based around, for example, crowd-pleasing stunts–encouraging both player and player character to do stupid, difficult, dangerous things that nonetheless make narrative sense.

♦ ♦ ♦

Of course, it’s always more complicated, and in the real world one has to consider motivation in the context of other narrative factors and gameplay as a whole. As with our last discussion (on Character, Viewpoint, and Audience Sympathy), we’re not even beginning to address the question of what happens when you introduce multiple player characters, or what happens when you partly hide a player character’s motivations from the player (the player character, a Secret Service agent, must get the president safely away from Russian agents… only to reveal that, previously unknown to the player, she’s in on the Russian plot!); suffice it to say that the principles remain, but applying them becomes much trickier.

Nonetheless, player motivation is something that must be considered at every stage of the game writing process. As outlined above, it’s vital when developing high-level story outlines, but it also comes into play on the detail level, with individual game systems and quest objectives and even branching conversation options (it doesn’t matter if every conversation choice is in-character if none of them match the player’s motivations–but splitting “player-driven options” from “player character-driven options” has problems as well!)

Know your players and understand what they’re bringing to the game. Know your characters and what drives them. And remember it all, for every step of development, for every mission and line of dialogue.