This is the fourth part in a multi-part series on branching conversation systems (crossposted at Gamasutra.com). See the Introduction for context.

You have the tools. You know how to structure a conversation so you can work with and maintain it across a game’s full development cycle. Now… how do you make that conversation good?

This post attempts to summarize some key principles to keep in mind throughout the writing process. Some of these principles are obvious but nonetheless important–it’s surprisingly easy to lose sight of storytelling fundamentals when focusing on the complexities of branching. We’ll get into greater specifics next time, but the ideals below should suffuse everything you do.

Know Your Star

Many writers fall into the trap of using the Player character primarily to draw out an NPC’s personality. The NPC is witty or angst-ridden; the Player’s responses prompt the NPC to display her engaging self in a variety of ways. It’s a seductive approach, given that the Player character’s personality (being under the control of the Player) is by nature ill-defined.

But in most games (and if you don’t think it’s true in yours, be absolutely sure), the Player character is still the protagonist and undisputed star. NPCs are supporting cast members at best, and more frequently walk-ons. If your game were a film or a novel, your Player character’s desires, reactions, and concerns would be the driving force of any given scene.

The Mass Effect series excels at making the Player character feel like the driving force of each scene. (Screenshot generously provided by @LechucksBeard.)

The Mass Effect series excels at making the Player character feel like the driving force of each scene. (Screenshot generously provided by @LechucksBeard.)

Games are games, of course–not novels or films–but that only makes this subject more important. The Player character, in most types of games, is the utterly dominant presence. That’s the nature of video games–Players empathize with their characters in a uniquely powerful way. Everything is seen through the Player character’s eyes (literally or figuratively). Everything is secondary to the Player character’s needs.

Therefore, the standard lessons every writer already knows apply: most of the time, a given scene (such as a dialogue sequence) should put the Player character at the center of the action. The Player should feel like she’s driving the conversation through her response options. The Player should feel like the NPC serves to further her story. The Player should feel like she has the best lines and coolest moments (Players aren’t fond of being upstaged). Picturing a version of the scene without the Player character should be virtually impossible.

There are always exceptions, of course, and you don’t want to shortchange an NPC–making the Player character the star isn’t an excuse for ill-developed secondary characters. And different styles of games put different amounts of emphasis on the Player character as a true personality (as opposed to as an avatar or filter for the Player). But it’s often helpful to ask yourself–particularly in games with voiceover and cinematics–“If this conversation were in a book / film / comic / whatever, would it de-protagonize the protagonist?”

Plan Ahead

Every writer has his own process, and while I’m exorbitantly fond of outlines, some writers only feel comfortable working without a net. There’s nothing wrong with that…

…yet I encourage any writer who wants to work with branching dialogue to plan conversations ahead of time, at least in the beginning. Without a plan, It’s too easy to let branches spiral out of control and to forget what information the critical path of the conversation must contain.

For my own work, I like to get a clear idea of what every set of Player responses is going to reply to (even if I’m not sure of all the responses individually in advance). I like to know where I’m going to need substantial branches, and of course I want to understand whatever I need to communicate to the Player for the next sequence.

You may plan in more or less detail, but really: Try planning ahead. Don’t get bogged down needlessly.

Choices are Rewards

Let’s look at two different metaphors for Player response options.

In our first metaphor, Player response options are a crank that the Player must turn in order to push a conversation (and thus the narrative) forward. The conversation is genuinely entertaining and the response options still important–disgorging so much text without Player interaction would be tiring at best–but the act of choosing a response is the conversational equivalent of a quick-time event. It’s busywork to keep the Player feeling engaged.

In our second metaphor, Player response options are the buttons on a vending machine. The NPC’s portion of the conversation is entertaining, but just as exciting is the loose change the Player receives for every NPC line that passes. Player response options are the Player’s chance to spend that change and get something awesome.

You can probably guess which metaphor I favor.

Make every Player response option awesome. The outcome of any given choice doesn’t need to be beneficial, but it should always make for a compelling and memorable story. If responses are just busywork to get necessary information from an NPC, then what’s the point? Let them serve as an opportunity for the Player to express herself and her vision of the Player character, the character’s story, and the themes surrounding that story–and then build on what the Player is telling you she wants.

I’ll be honest–this conversation from The Witcher 2 doesn’t have much to do with anything. I just needed to break up the text and didn’t have anything more appropriate.

If the Player is choosing villainous responses, she wants a story about villainy. Give it to her (in whatever form you as the writer feel is most appropriate–you’re still in charge). Make the Player excited to get response options because she knows they’ll pay off with something interesting.

(This principle, incidentally, is another reason I’m not especially fond of question hubs–hub-and-spoke segments of a conversation which consist solely of the Player character demanding “Tell me more about X” and the NPC obliging. It’s not that a question hub can’t deliver compelling options and rewarding responses–but doing so is an especially difficult endeavor.)

Scenes are Scenes

Remember your writing fundamentals. Video game conversation scenes are still scenes. They should be dramatic. They should push the narrative forward in plot, character, theme, or all three. They should have a pace and a rhythm, building to a climax and then ending without wasting time. They should start with a clear hook to capture the audience’s attention. Yes, there are always (always!) exceptions, and yes, games work differently than traditional media–but scenes are still scenes.

Don’t get so caught up in making a conversation functional–in making sure that it delivers all the right critical path information to the Player, in making sure the Player has sufficient options, in making sure that the Player knows and understands what her next gameplay step is–that you forget to make the narrative work on a more basic level. If you rip all the choices out and pick one linear path for the conversation, does it make for a compelling piece of drama?

Every Choice Matters…

The worst way you can approach branching narrative (and branching dialogue) is to think of it as a “trick”–a way to make the Player believe she has choice and agency when in fact, she’s just going down the path you’ve set for her.

“But don’t most branches merge?” you may reasonably ask. “In fact, don’t most Player choices lead to only a handful of distinct NPC lines before folding back into the critical path? How is that not tricking the Player into thinking there is choice where no choice exists?”

To which I say two things:

First, when it comes to the choices that don’t “matter”–the ones that merge back into a critical path without long-term consequences–giving the Player a choice of how to characterize the protagonist means letting the Player choose the lens through which the narrative is perceived. Think of simple, “role-playing” response options as a thematic filter–the Player who chooses tragically brooding lines instead of smart-alecky ones in your vampire game is shifting the basic ideas that your game explores.

This is another reason why it’s vital to understand that the Player character is the star and the protagonist. Your conversation scenes are about the Player character, not the NPCs, and story derives its meaning from who the protagonist is.

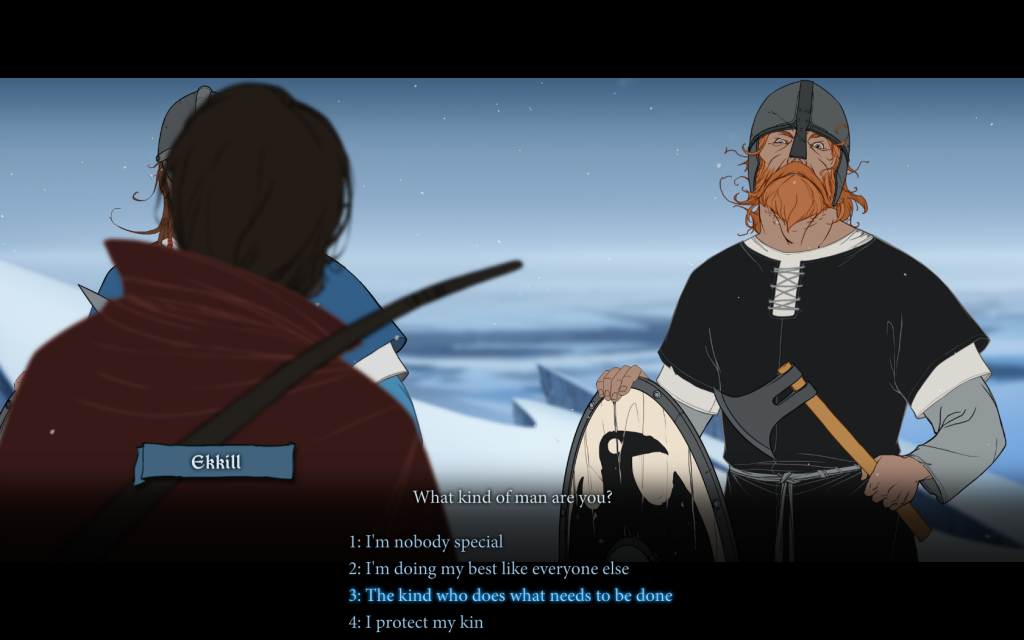

A role-playing moment from The Banner Saga allowing the Player to reflect on larger themes.

A role-playing moment from The Banner Saga allowing the Player to reflect on larger themes.

Would Star Wars be the same story if Luke Skywalker turned cold and vengeful when his parents died and spent the rest of the movie in mourning, dwelling constantly on the human cost of space warfare and loathing the evil Empire? You could use the same plot–he could still go to the Death Star, rescue a princess, and destroy the enemy–but the audience would come away in a very different mood and with a very different sense of the film. The movie would be about something different. (In fact, the mere presence of different options, even if never chosen, frame a story’s themes and central conflict in a new manner.)

That’s why the choices that don’t matter still matter. They define the audience experience. Yet choices matter even more when they do have long-lasting consequences, which brings me to my second point…

…But Make Sure Your Biggest Choices and Consequences are Visible

When a substantive branch occurs–whether it lasts for a conversation or the remainder of the game–make sure the Player understands that the branch is happening. All the little choices that “don’t matter” serve as a force multiplier for the impact of these larger branches, but that multiplier is lost if the Player still thinks she’s been railroaded onto the critical path.

Making choices visible can be accomplished in a number of ways. For starters, make sure you’re signposting big decision moments adequately. Having a major NPC betray me late in the game because I was slightly rude to him near the beginning doesn’t make me feel like my choices have consequences–it just makes me feel like I live in a fickle, unpredictable world where I lack any real agency. I probably don’t even remember being rude to the character, and assume the betrayal was going to happen regardless.

On the other hand, if I receive an emphatic warning from the NPC’s brother before talking to him–“NPC Y is incredibly fickle. If you need to be rough with him, go ahead, but god only knows what wheels will start turning in his head.”–and the betrayal comes soon enough that I still remember the encounter, the sense of choice and consequence is much more powerful.

In addition to narrative signposts, make sure your Player response options are clear when the big moments come. You don’t want the Player casually picking the snarky option, figuring it’ll be funny but won’t matter, when that’s the choice that will determine whether the huge diplomatic treaty will be signed. Make sure your response options are bold and distinct from one another, whatever interface and system you’re using. (For your biggest moments, you may even want a “are you sure we should do that?” reply from an NPC to allow the Player to backtrack if needed. “Wait, no, I meant ‘commit genocide’ sarcastically. Yes, let’s sign the treaty.”)

Finally, part of making branches visible and feel consequential is picking where not to branch. You and your team only have so much time and effort to put into your game. When you create a branch, make it as beautiful and compelling as you can, and don’t distract yourself with other elaborate branches in minor scenes that Players will forget an hour later. Players will forgive a lot of limited choice if the most dramatic scenes in the game diverge in a variety of powerful ways… and they’ll never forgive you if they feel their agency has been taken away at the biggest moments, no matter how many minor branches you create along the way.

Characters are Characters

Again, remember your writing fundamentals. Characters should have distinct voices, should enrich our understanding of the protagonist or the story’s central themes, should have their own motivations and desires (that may be different from those of the Player character and may contradict what they say aloud). They should be as memorable as their role and the narrative support–walk-on characters shouldn’t upstage the supporting cast, but a dollop of humanity and dignity never goes amiss.

The colorful characters of the Wing Commander series brought emotional weight to a straightforward war story. (Wing Commander 3, pictured, was the first to use branching dialogue.)

I’ve seen talented writers forget everything they know when they begin game writing, creating “Ho, adventurer! I have a task for you!”-style quest dispensers, as if the NPCs have no lives or desires other than flagging down the first Player character they see. Don’t be one of those writers. Yes, if your game is laden, RPG-style, with one-off characters designed to provide quest content, you’ve got a challenge justifying why all these NPCs are on the Player’s path and crying for help–but remember to look at what you’ve done in all its sparkling game design functionality and ask, “Does this character justify his existence in the story?”

Know Your Player Archetypes

In part two, we discussed (under “Number of Options”) the need to figure out the most common personality types your Players will apply to their Player characters. This will, of course, be dictated by your genre and the particulars of your narrative–not many Players of your high school drama RPG will expect to be able to play a bloodthirsty psychopath, and not many Players of your space marine shooter will expect to be able to play as a shy wallflower–so give it ample consideration. Make sure that the types of characters, stories, and themes you support (by virtue of your response options, your gameplay, your supporting cast, and so on) match the Player’s expectations; if you don’t, you may end up with frustrated Players very quickly!

(Setting those expectations is best done before character creation–introductory sequences are useful here–and by out-of-game marketing. Why did your Player buy the game? What sort of experience did she expect? If you don’t offer that experience, of course you’ll have a problem.)

Let’s go back to that high school drama RPG for an example. Off the top of my head, I’ll want to support protagonists with the following characteristics:

Athletic, Smart, Witty, Ambitious, Slacker, Geeky, Brooding, Outcast, Male, Female, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender…

Note that while I’ve got “Smart” on the list, I didn’t put “Stupid”; while Players may not want to play an intellectual character, I feel like very few Players will be bothered that they can’t play a character who’s incapable of being smart. (Which isn’t to say you couldn’t have “Stupid” as an option, but will Players really feel like their experience has been negatively impacted without it?) I didn’t put “Power Hungry” either, because it’s not that sort of game or genre.

When I’m writing a scene, I should ask: does a Player character built from any combination of the above attributes get to act appropriately? This isn’t just about individual Player response options, but about the flow of the conversation as a whole. While yes, it’s important that my brooding character not be faced with an array of only cheerful options (no matter how different the options otherwise are), it’s also important that my athlete not converse with an NPC who breezes past a discussion of the school sports team to start talking about his parents. My Player character cares about the team, and would definitely have something to say about it!

In short, construct whole conversations with an eye to all viable Player characters who could be taking part. What motivates your protagonist is key to your story; don’t fail to acknowledge those motivators!

Mind the Players Who Don’t Care

How do you handle a Player who isn’t interested in narrative?

For some sorts of games, the answer is “You don’t.” If I’m writing a Japanese-style visual novel or a text-based Choose Your Own Adventure-inspired app, I’m not going to bother catering to Players who don’t care.

But what if I’m writing a first-person shooter with RPG elements, or a puzzle game with occasional narrative breaks? If most of what a game has to offer is non-story-and-character-based content, then how do I address the needs of those Players in dialogue?

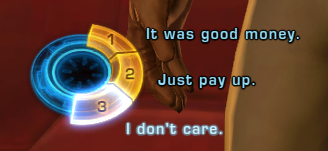

A dialogue wheel from Star Wars: The Old Republic.

In such a case–assuming you don’t have mechanics that allow the Player to bypass conversations altogether–make sure you’ve got a clearly marked direct line through the critical path of the conversation. If you’ve got a “default” Player response option, it probably leads down this path; if you’re making the disinterested Player hunt for the right option to get out of the conversation quickly, you’re sort of missing the point.

Of course, your “shortcut” through the conversation still needs to be well-written. It’s most likely appropriate to a straightforward and focused Player character–the “man of action”-type in a shooter–which is an archetype you probably want to support anyway. In other words, the path for Players who don’t care, if done right, also serves a large number of Players who do.

Coming Up Next

We discuss ways to apply these principles on a line-by-line level and other tips and tricks for branching dialogue writing. We ask (and answer) questions such as “How often should the Player be given response options?” and “How should those options be differentiated?” in what is (tentatively) our final installment.