I’ve totally neglected my game writing posts, of late–I’ve got a number of articles half-composed, with titles like “Writing for Failure” and “Complex Stories and Atomic Narrative Theory.” Unfortunately, paying work has taken precedence over more complex pieces, so let’s do something simple: Back to writing fundamentals!

Games–especially open-world action-adventure games and role-playing games–tend to have extremely large casts. This is partly due to length (you can cram a lot of characters into a 40-hour game), but mostly due to mechanics: If every quest requires a unique quest-giver, or if every town needs to be populated with a dozen or more conversable NPCs, or if every item seller needs dialogue attached, you’re going to end up with vastly more characters than the narrative really warrants. When it comes to speaking roles, a game like Dragon Age: Inquisition makes the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy look intimate and focused by comparison.

Let’s forget mitigating this fundamental issue for now (and there are ways to design games to reduce this problem) and focus instead on how to handle all those characters. We’re not just dealing with a cast of thousands, but a cast of a thousand walk-ons–characters who appear for one scene, serve one purpose, and then may never be seen again. Continue reading →

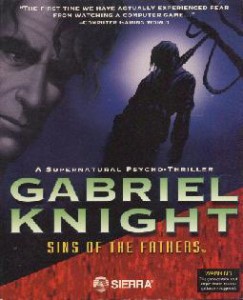

nged. The adventure game genre is still around, but is no longer a dominant industry force. Now even first-person shooters and other action games are marketed with a strong emphasis on story.

nged. The adventure game genre is still around, but is no longer a dominant industry force. Now even first-person shooters and other action games are marketed with a strong emphasis on story.